This essay was entered into the St Hughes Mary Renault essay competition. It was commended for its “well structured and well researched essay” that the “judges enjoyed reading”.

The Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones was besotted with the classical world, as a result of his Oxford schooling, his trips to Florence, Rome and Venice, Britain’s prominent role in the nineteenth century revival of antiquity and his Grecian mistress[1]. This infatuation is best shown through the majority of his paintings having classical subjects which either draw from ancient sources, such as Ovid, or his contemporary William Morris’ retellings. In this essay I argue that Edward Burne-Jones’ treatment of classical mythology is multi-faceted, as he portrays the events of the myths accurately, replicating classical artistic ideals as he does so, but also uses them as vehicles to justify and make sense of his illicit extramarital affair. In order to do this, I shall explore three paintings by the artist, namely: ‘The Doom fulfilled’ 1888, ‘Pygmalion and the image: The Godhead fires’ 1878 and ‘Phyllis and Demophoön’ 1870.

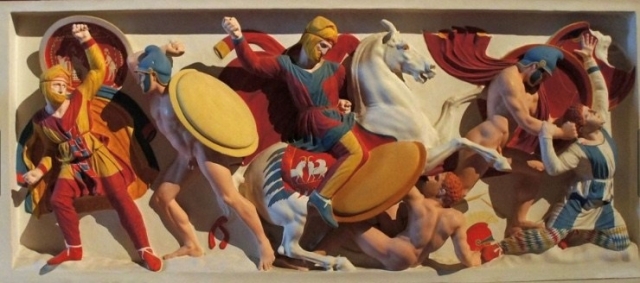

In ‘The Doom fulfilled’ 1888, Burne-Jones both glorifies classical art, by drawing inspiration from and replicating its techniques and appropriates it by corrupting its purpose as an exemplum virtutis by linking the artwork to his prior affair. Andromeda is presented with pale translucent skin, reminiscent of the preferred medium for classical sculpture, marble. Her white skin glows in comparison to Perseus’ olive complexion, drawing on the idea of gendered colours that was evident in antiquity. Whereas pale skin was considered the epitome of female beauty, warriors were often described as having a darker skin tone, as shown by Homer’s description of Odysseus becoming melagkhroiēs (black-skinned) again. Furthermore, Andromeda stands in contrapposto, harking back to classical nude statues such as the Praxitelean type, Venus of Cnidus 350 BCE, which the artist was known to have studied carefully[2]. Moreover, the figure of Perseus is directly based off the Laocoön. Both stand contrapposto in their attempts to feign off the attacks of vicious sea serpents which have coiled between their legs, with the snake’s frozen mid bite. Both men visibly strain to fend off their mystical attackers with Perseus’ arms heroically outstretched to resemble Sansovino’s, now deemed incorrect restoration of the statue. By drawing so greatly on the Laocoön for inspiration, Burne-Jones is echoing Pliny the Elder’s musing that the sculpture “is a work of art to be preferred to any other painting or statuary[3]”. In this way, the artist shows great respect for art from the classical period, by using similar techniques and repurposing subjects to replicate both the aesthetics and the esteem of classical art. However, this painting subtly alludes to his long-term affair with the sculptress Maria Zambaco Cassavetti, described as the “emotional climax of his life”[4], and he therefore appropriates the classical world’s use of art as an exemplum virtutis. The violent imagery of the Perseus saga acts as a manifestation of the extremely passionate affair between Burne-Jones and Cassavetti, which was epitomised by their 1869 suicide pact to overdose on Laudanum together[5]. Burne-Jones used Maria to make his last studies for the female figure, as he saw her as an ideal Grecian beauty and therefore more beautiful than the Nereids, just like Andromeda was claimed to be by her mother. However more implicitly, Burne-Jones takes on the mythical role of Perseus as he reflects on societies negative perception of his affair and his inner turmoil between loving his wife and craving his mistress, which are both embodied by the snake he is fighting. The all-encompassing effect of his affair and its negative ramifications are further reflected on by the choppy, inky waves and the desolate rocky background that encircle and trap the two subjects. Interestingly, Burne-Jones’ choice to portray the Perseus saga was most likely in part to the myth’s love triangle between Perseus, Andromeda and her previously betrothed Phineus and its similarities to the love triangle between Maria, himself, and his wife Georgiana. Although Burne-Jones was not a hero like Perseus as the sensibilities of Victorian society condemned affairs especially when overt. He therefore appropriates and corrupts the morally sound myth of a hero protecting a maiden, using it to exonerate himself by portraying himself and Maria, the perpetrators, as beautiful and idealised classical sculptures.

In his ‘Pygmallion and the image’ series of 1878, Burne-Jones appropriates the Greek ideal of beauty, which he tried so hard to replicate, by using his ex-mistress as his model for the female figures. In the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea, which the image is based on, Pygmalion sculpts his ideal of female beauty and then begs Aphrodite for a wife as perfect as his marble woman. This tale is mirrored in Burne-Jones’ personal life, as although he thought he was already married to the perfect woman, he could not help but long for his muse Maria. This is exemplified by Maria being used as the model for both Aphrodite and Galatea as she was the living embodiment of Grecian beauty by the Pre-Raphaelites. Her “glorious red hair” is shared by the goddess Aphrodite in the painting, and her “almost phosphorescent white skin[6]” that likened her to the “white-armed Helen”[7] of the Iliad and Odyssey, is shared by both figures. Crucially however, as with all other epochs that aimed to recreate authentic classical beauty, the Pre-Raphaelites failed as they projected their modern bias onto the past. Burne-Jones once mused that, “I must confess that my interest in a woman is because she is a woman and is such a nice shape and so different to mine.”[8] This contrasts greatly to the androgynous concept of Apollonian beauty where harmony consisted in opposition, namely, between that of male and female[9]. Furthermore, the ancient Greek view of beauty was multi-faceted as it was as much to do with the qualities of the soul and personality, as well as physical appearance. Kalokagathia, literally καλός kai ἀγαθός meaning beautiful and good, encompasses the beauty of forms, the goodness of the soul and the morality of character into one expression[10]. In this way, Burne-Jones fails in his quest to replicate classical beauty in his paintings; as his model Maria cannot be deemed as kalokagathia. She was an adulterer on two counts, against her own estranged husband Demetrius Zambaco and Georgiana Burne-Jones and is therefore not virtuous. Consequently, by using Maria as his model he is appropriating the classical ideals he is trying to replicate. The artist therefore overcompensates by flooding the image with the symbolism of Aphrodite, and therefore beauty and love. The goddess stands in a pool of crystal aquamarine, which harks back to her creation of being fully formed from the sea. She is also portrayed surrounded by doves, her avian symbol, following in the classical artistic tradition which can be seen on Greek pottery and on reliefs of her temples such as that of Aphrodite Pandemos at Athens[11]. Furthermore, she is adorned with both roses and a myrtle branch, of which were sacred to the deity. However, as myrtle was classically used in wedding rituals, even Burne-Jones’ compensation subtly alludes to his 1869 plan to leave his wife in order to marry his mistress. Indeed, this image was inextricably linked to his affair as Burne-Jones even sent the first set of his ‘Pygmallion and the image’ series to Maria Zambaco’s mother[12], despite no longer being romantically involved with her. Therefore, Burne-Jones greatly appropriates the Greek world and its ideals in this image as he fails to replicate the Greek concept of Kalokagathia and recontextualises the myth of Pygmalion and Galatea in order to beautify the sordid reality of his affair.

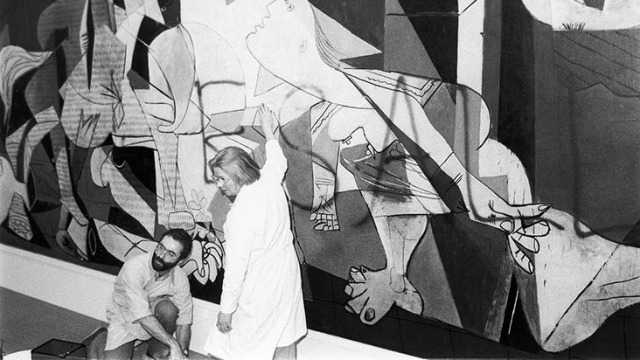

This first edition of Burne-Jones’ painting ‘Phyllis and Demophoön’ from 1870 is wrought with references to his affair and is thus an appropriation of the eponymous myth rooted in espousal loyalty. In 1870 his affair with Maria was coming to a physical end as the guilt he felt towards his wife Georgiana and his two children triumphed over his infatuation. This regret is encapsulated by the caption he gave to this image in the Summer Exhibition catalogue of the Old Watercolour Society, “Dic mihi quid feci? Nisi non sapienter amavi”, a quote from Ovid that translates to “Tell me what I have done? I loved unwisely”[13]. This painting’s subject matter can be interpreted in multiple ways, it could be a physical embodiment of Burne-Jones’ difficult escape from his long-term affair, as Demophoön seems eager to flee from Phyllis, modelled off Maria, who has ensnared him with both her arms and her drapery. However, as mythically Phyllis is a loyal wife whose tale is recounted second only to Penelope’s (the most loyal woman in Classical culture) in Ovid’s ‘Heroides’, the female figure more likely represents Georgiana, wife of Burne-Jones. If we interpret the image accordingly, Demophoön looks back mournfully to the woman he has hurt, and his kinetic stance is due to the shock he feels in being welcomed back so readily and warmly. In the myth Phyllis kills herself from heartbreak and loneliness as a result of her husband never returning home, similarly Georgiana describes the years of her husband’s affair, 1868-71, simply as “Heart, thou and I here, sad and alone”[14]. As there were multiple similarities between the classical world, especially its myths, and Burne-Jones’ personal life, it was near impossible for him to not replicate elements of the classical world in his paintings. The female figure’s face takes on the likeness of the blooms around her as it is illuminated with a pink glow, juxtaposing the two faces in terms of light, establishing the female as the virtuous and the male as the sinful. His use of the colour pink has classical connotations of “rosy-fingered Dawn”[15] . The hope that the female deity inspired in her creation of a new day, is akin to the hope Georgiana inspires for a reunification. Moreover, the drapery is not diminishing in its connection with Demophoön but growing, as it represents the connection between man and wife. This was previously only felt by Georgiana, being gradually shared by Burne-Jones. This reinvigoration of marital unity is further emphasised by their shared mossy and shadowed skin tones, achieved by Burne-Jones through chiaroscuro, as they become one both emotionally and physically. Despite the end of his affair with Maria, Burne-Jones continued to use her likeness in his later paintings, including the two I have previously explored, as regardless of their relationship status she remained his epitome of Grecian beauty. Therefore, whilst Burne-Jones does appropriate the classical world and its ideals in this image, as he corrupts the figure of the loyal Phyllis with the head of his mistress, all images after this are mere reflections on his affair and therefore more passive in their appropriation.

In reviewing these three works by Edward Burne-Jones, I can ascertain that the artist both replicates the classical world and its ideals as he portrays the events of the myths accurately whilst using the techniques of classical art, but also appropriates the classical world and its ideals. Specifically, the moral purpose of art, mythology and the concept of beauty. Nevertheless, whilst the morality of appropriating art, and its subjects, is fiercely debated, Jean Pierrot alludes in his ‘The Decadent Imagination: 1800-1900, that the classical world provides a framework for artists to express their personal ideas and or problems, safely behind the veil of antiquity. Indeed, the beauty of Classics is in its ability to be received and utilised by a plethora of people in a multitude of ways, including Edward Burne-Jones’ use of mythology in his artwork to make sense of his illicit personal affairs.

[1] Liana De Girolami Cheney. “Edward Burne-Jones’ ‘Andromeda’: Transformation of Historical and Mythological Sources.” Artibus Et Historiae, vol. 25, no. 49, 2004, pp. 197–227. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483754.

[2] Liana De Girolami Cheney. “Edward Burne-Jones’ ‘Andromeda’: Transformation of Historical and Mythological Sources.” Artibus Et Historiae, vol. 25, no. 49, 2004, pp. 197–227. JSTOR, accessed from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483754.

[3] Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 36.37

[4] Stephen Wildman, Edward Burne-Jones: Victorian Artist-Dreamer, MET Publications, 1998, p114

5 Jan Marsh, Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood, Interlink Pub Group Inc, 1985, p273

[6] Alexander Constantine Ionides Jr, Ion: A Grandfather’s Tal, vol.2, notes and index, p28

[7] Homer, Iliad, 3.121

Homer, Odyssey, 7.357

[8] Penelope Fitzgerald, Edward Burne-Jones, Sutton Publishing Ltd,1975, p115

[9] Umberto Eco, History of Beauty, Rizzoli, 2004, p58 & 72

[10] Ibid p45

[11] Monica S. Cyrino, Aphrodite, Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World, Routledge, 2010, p122

[12] Ann S. Dean, Edward Burne Jones, Pitkin Guides, p19

[13] http://www.bmagic.org.uk/objects/1916P37 accessed: 15/06/2019

[14] Georgiana Burne-Jones, The Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones, Volume 2, 1904, Ch XVI

[15] Homer, Odyssey, 2.476